Toolkit and Films

Introduction

Most of the ETF’s 29 partner countries have National Qualifications Frameworks but these are mainly on paper or only partially implemented. This toolkit examines why countries are blocked and proposes solutions to speed up implementation. We go wider than NQFs.

To tackle problems in implementing an NQF requires us to address the four key elements in a qualification system: laws, stakeholders, institutions and quality assurance. So our focus is on the qualification system and making it work.

Chapter summaries

Summary

Chapter 1.

Qualifications and qualification systems – Policy stages: Self- assessment tool – Where are we?

In order to make effective system-wide and system-deep reform there needs to be a clear understanding of the distinction between the term ‘national qualifications framework’ and the qualification system as a whole. This toolkit is not about NQFs per se, but about qualification systems. Qualification systems are effective if the organisational arrangements which comprise them work together to ensure that more individuals have access to, and can choose and obtain qualifications that are t for purpose, meet the needs of society, and o er opportunities for employment, recognition, career development, and lifelong learning. These organisational arrangements are not usually implemented systemically or in a linear fashion, but rather organically over time. They have strong interdependencies and should be viewed as part of a common system of governance (or, organisation) of qualification systems. The factors that are explored here are legislation, stakeholder involvement, institutional arrangements, and quality assurance.

Chapter 2.

Legislation for better qualifications: support or obstacle?

Legislation is a fundamental enabler of the production of

better qualifications. We look at eight key parts of legislation for a systemic approach towards better qualifications, starting with the basic purpose and principles involved, and covering the main components that laws are designed to regulate. Examining the legislative process reveals the importance of aligning old and new legislation and highlights key differences between primary and secondary legislation. Different legal and cultural traditions inform the way countries strike a balance between tight and loose legislation, and influence accepted ways of involving stakeholders. Critically, the discussion turns to how to ensure that legislation can be implemented. Drawing on research into legislation in eleven countries, we refer to a range of legislative processes, participants, and outcomes that concretely illustrate what can otherwise be a somewhat abstract discussion.

Chapter 3.

Stakeholder involvement: in or out?

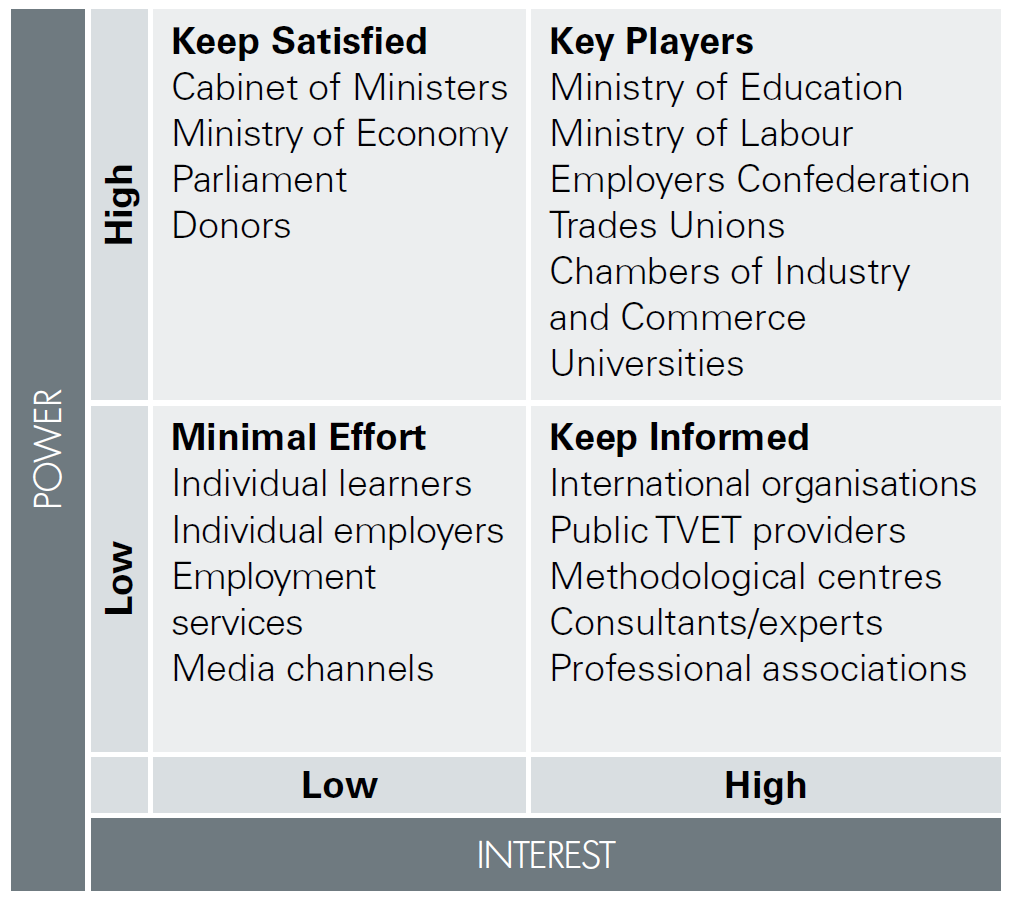

Stakeholder dialogue should articulate labour market actors’

and other stakeholders’ needs to contribute to qualifications that are relevant to the labour market and attractive to the learner. Finding the right balance between top-down and bottom-up in the direction of stakeholder communication will depend on which group or groups initiate and develop the process. With the identification and inclusion of stakeholders, new partnerships can be built to produce better qualifications, and decisions made at policy level can obtain the necessary credibility to see them through the design and implementation stages. There are many different forms of dialogue between stakeholders, and existing methodologies and best practices can be adapted to t the environment of qualification system reform. Distinguishing between stakeholders with differing levels of interest in, and power to a ect reforms is vital, as is differentiating between dialogue platforms and implementing bodies. Stakeholder engagement is a marathon, not a sprint. You have to be in it for the long-run.

Chapter 4.

Institutional arrangements: bureaucracies or service providers?

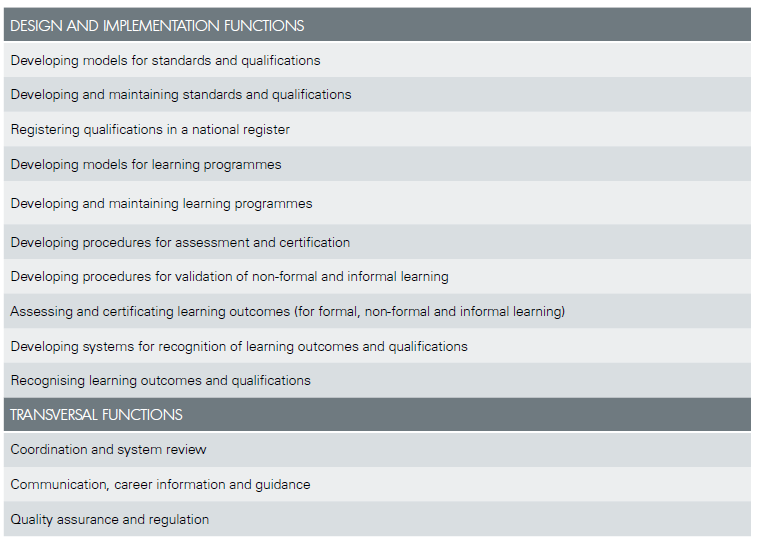

What do fit-for-purpose arrangements for implementing a qualification system look like? The different institutional functions and roles are wide-ranging, including:

- Communication and career information and guidance

- Coordination, system development, and review

- Development and maintenance of standards and quali cations

- Development of provision and learning including curricula and programme development and learning methods

- Establishing and managing a national register

- Quality assurance and regulation

- Recognition

- Summative assessment and certification

- Validation of non-formal and informal learning.

The roles of key ministries, particularly education and labour, and other public governing bodies such as councils and boards, specialised agencies, providers, awarding bodies, and assessment centres need to be clearly specified and monitored in the implementation of a reformed qualification system. Making a functional analysis of existing institutional arrangements will reveal what’s working and what needs to be changed, including exploring advantages and disadvantages of establishing specialised bodies and combining functions within the implementation of a qualification system. The creation, or evolution, of specialised agencies requires careful examination of resource implications, but the existence of a dedicated group of professionals may considerably speed up implementation.

Chapter 5.

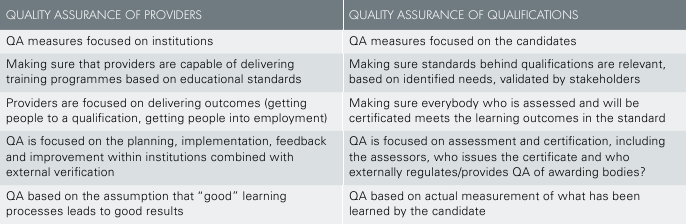

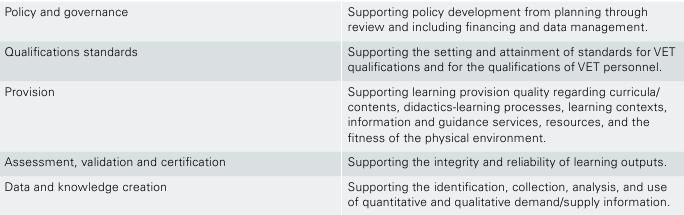

Quality assurance for qualifications: empowering or controlling?

Assuring the quality of qualifications requires dialogue among a range of actors, proportionate legislation, and clear institutional roles and functions. Here, we do not cover every aspect of the vast field of quality assurance. Instead, we examine how countries ensure that the qualifications that are used are relevant and have value in the labour market; and how countries can be sure that the people receiving certificates are meeting the conditions of these qualifications (in other words, they have demonstrated that they meet the standards). In particular, we examine the QA procedures used to regulate the inclusion of qualifications into qualifications registers, the use of NQFs in gatekeeping, and how assessment is quality-assured. This may include, for instance, the extent of external assurance and the qualifications of the assessors, and how validation of non-formal learning is assured. We try to gauge how far different countries’ assessment and certification practices rely on trust and self-regulation, and whether they use more cooperative models or apply more tightly-regulated systems.

Introduction

Summary

- Implementing NQFs – countries at the crossroads

- Why countries are blocked

- Structure and themes of this toolkit

- The self-assessment tools (SATs)

1. Implementing NQFs – countries at the crossroads

Our partner countries, 29 EU neighbourhood and enlargement countries, are at a crossroads. Most have NQFs but these are either largely on paper or only slowly being implemented. Countries to need to speed up their NQFs. After an initial surge 5 or 6 years ago in most cases, the momentum is slowing. Most of the countries aiming at an NQF have a consensus to proceed, have NQF laws, and have allocated roles to institutions. Some have developed implementation plans, designed quality assurance systems and have developed criteria for structure and content of qualifications. Some have been piloting new methodologies and qualifications. A vanguard group has established or designated bodies to lead qualification system reform. There are numerous donor-funded projects but it is often difficult to apply their outputs in national systems. A few are already at the real implementation stage where they have qualifications in their framework levels. These are significant advances.

But a broad majority are somewhere in the middle – their NQFs are partially implemented. This is frustrating for them. They may question the value of NQFs. But most agree an NQF is useful- they see NQFs working in some partner countries and they grasp that there is no going back. This toolkit assesses why they are in this position and formulates proposals to break through the gridlock.

As countries have plans, understand the value and purposes of NQFs and have produced some standards, their real challenge is not the software of outcomes, and qualifications design, but the hardware. This is the infrastructure of a qualification system: the laws, stakeholders, institutions and quality assurance systems. So, in this toolkit we analyse how EU member states and EU neighbourhood countries organise their qualification systems to produce better qualifications, and how they are seeking to re-structure to support reform. We look at the systems, institutions, actors, and processes involved, and how regulation and legislation, stakeholder interaction, institutional arrangements, and quality assurance arrangements contribute to improved qualifications. This offers our partner countries some examples which can inform decisions about institutional arrangements and legislative frameworks.

Countries are developing qualifications because they want better qualifications. Better qualifications are necessary because learners and workers need a trusted way of demonstrating their competence to perform a job, in a world of increasing mobility and career change.

We do not underestimate the challenge of reforming qualification systems to produce better qualifications. ETF’s engagement with our partner countries is long-term and deep. These 29 countries are societies and economies in transition. We know that they face the same challenges as other countries but with the added difficulties of political and economic upheaval. These challenges have strained VET systems, as most countries have moved from mainly state-run VET systems supplying command economies with a predictable stream of VET graduates in stable employment, to more complex economies with unpredictable job prospects and more diverse provision. These countries are, therefore, seeking to improve their qualifications. They have been looking to the NQF as the principal tool to fix the qualification problem.

This challenge is urgent and daunting. Many of the established initial vocational qualifications have become obsolete. New private providers, and new programmes in higher education and adult learning, offer qualifications with titles that may sound attractive to learners but which employers do not understand. Many qualifications bear little relevance to labour market needs, with employers only infrequently engaged in their design or assessment. Instead, ministries or schools develop them without consulting social partners. They are often designed around programmes or course hours, so that what learners can actually do after obtaining a certificate is not easily understood, nor can their qualifications be easily compared, within and across countries.

Additionally, in too many countries the range or type of qualifications is limited, so that the only vocational qualifications available are aimed at young people in full-time education and training. Adults, jobseekers, and others looking for flexible, smaller or more specialised qualifications are often not catered for. In many cases modern governing structures or organising systems, such as specialised VET agencies or qualifications authorities, sector skills councils, and quality assurance systems, are still in their early stages, if they exist at all.

However, we should also note that our counterparts in the partner countries – experts, officials, stakeholders – acknowledge the scale of the challenges, and understand what needs to be done. They have made considerable strides in introducing learning outcomes in some qualifications, in their use of occupational standards, and in planning and establishing national qualifications frameworks. Most are moving in the right direction and understand what needs to be done.

3. Structure and themes of this toolkit

The toolkit is structured to open up and discuss issues and describe country experiences in a series of chapters, each intended to capture one dimension of organising qualification systems. The whole should, therefore, result in understanding of how governance (including legislation, stakeholder involvement, institutions and quality assurance mechanisms) produces more relevant and higher quality qualifications.

Chapter 1 looks at meanings and understandings of qualifications; how we distinguish between traditional and modern qualifications; the influence of NQFs on re-structuring qualification systems; and how old and new components co-exist in some countries. Achieving the aim of high-value qualifications requires distinguishing between the different stages of development in countries’ qualification systems, whether initial, intermediate, or advanced. We also refer to some experiences in organising to deliver better qualifications.

Chapters 2 to 5 examine the four components of organising qualification systems. All these chapters, in keeping with our empirical approach, are derived from our observations and experience, and cite real cases. Each chapter ends with some brief conclusions, and recommendations to our partner country colleagues. We say what countries must have – not what it would be ideal to have – to make their qualification system function effectively to produce reformed and new qualifications.

Chapter 2 concerns the purposes, functions, and processes of legislation in a qualification system. We examine why regulation is important. We describe and examine cases of primary and secondary legislation in qualifications. This includes examining their scope, and the degree of prescription or latitude in partner countries, as well as how legislation can facilitate the active involvement of stakeholders or the design of institutional arrangements (roles and responsibilities).

Chapter 3 moves to the actors and other stakeholders involved, the bodies that connect VET and qualifications to the labour market, and identifies which stakeholders should be involved. We also identify institutions operating to engage stakeholders in qualifications reform, what instruments they use, and what roles such bodies play in qualification systems. This applies to social partners as well as to civil society organisations. We also look at the difference between dialogue platforms and implementing bodies.

In Chapter 4, we look in greater depth at the institutions which play a role in qualification systems, identify their functions, and examine the different set-ups between countries and the role of dedicated qualifications authorities. This picks up some of the themes pursued in Chapter 2. We look at the broadening of governance affected by NQFs; the eroding of ministerial monopolies in the coordination, development, and quality assurance of qualifications; and the emergence of new bodies, such as qualifications agencies, quality assurance bodies, awarding bodies, and sector skills councils that are established outside line ministries.

Chapter 5 is about how all the above is managed, controlled, and supported to ensure quality in the final ‘products’ – the qualifications and qualified individuals themselves. In a sense, this chapter addresses holistically the themes of Chapters 2, 3, and 4. Building a quality assurance system requires dialogue among diverse actors, designation of institutions, agreement on functions, and appropriate legislation and regulation. Note that we will not look exhaustively at every dimension of quality assurance, which is a vast field. In particular, we are not examining the quality assurance of providers, but focusing explicitly on the factors that determine the quality of the results of the certification process.

Chapter 6 distils the recommendations in the preceding chapters to sets of key messages, each set aimed at a category of actor in qualification systems.

Our recommendations in each chapter and our key messages do not point to a single model to copy. Instead, we underline common principles, based on a pragmatic, empirical analysis of what works better. In addition, we try to identify what sets of arrangements work well in a qualification system in the different national environments, as countries differ in size, economic strength, developmental stage, and institutional tradition and practice. And it is our fundamental belief that, despite all the complexities and difficulties of terminology and understanding, all of this matters – because qualifications matter.

4. The self-assessment tools (SATs)

A special feature of this new publication is the self-assessment tools, or SATs. These appear at the end of each of Chapters 1 to 5. The flap on the cover of this publication gives guidance on using the SATs. Each consists of a set of questions to be answered against a traffic-light system, which measures system progress, plus open questions for discussion. These questions and the responses to them will help to assess progress, reflect on current challenges, identify gaps in the system, and begin developing approaches and solutions. They can be complete as an individual exercise to begin reflecting on the issues. Perhaps their best use, though, is to gather key stakeholders in the country to use the SATs in a workshop or technical meeting. Already, in several partner countries, groups of experts, officials and other actors have organised workshops and used the SATs to facilitate discussions and identify actions. Such discussions can inform action plans, roadmaps, implementation strategies and new legislation or changes into existing ones.

Recommendations

• Focus on the organisational issues to implement concepts such as an NQF.

• This is urgent business. Act now or systemic change will not happen.

Chapter 1. Qualifications and qualification systems – Policy stages: Self- assessment tool – Where are we?

Summary

Duration: 1:59- Qualifications, qualifications frameworks, qualification systems

- A new understanding of qualifications

- New versus old ways of getting organised

- Competing ministerial agendas

- Making qualifications frameworks work

- Towards sustainable qualification systems

- Conclusions and recommendations

1. Qualifications, qualifications frameworks, qualification systems

While getting organised is complex and requires careful thought and precision, it is also urgent business for everyone concerned. We cannot over-state the lost opportunities that will arise if systemic change is not initiated, nor the lost benefits of revitalised and relevant qualifications to millions of people. To take this further in any given country context means addressing what we have called the hardware, the critical infrastructure for organising an effective and efficient qualification system. In order to make effective system-wide and system-deep reform there needs to be a clear understanding of the distinction between the term ‘national qualifications framework’ and the qualification system as a whole. We propose the following definitions:

National qualifications frameworks (NQFs) are tools which classify qualifications according to a hierarchy of levels, typically in a grid structure. Each level is defined by a set of descriptors indicating the learning outcomes applicable at that level. Levels vary in number as determined by national need. Qualifications are allocated to NQF levels based on learning outcomes. An NQF helps thus to classify the qualifications in order to distinguish and to link them. NQFs can have additional functions in terms of criteria for describing qualifications (e.g. by type, purpose, pathways, unit structures, or credit values) and for adopting qualifications to the NQF register. An NQF brings order to the landscape of qualifications. A national qualifications framework is thus a specific policy instrument that functions as a tool within an overall qualification system.

A qualification system is everything in a country’s education and training system which leads to the issuing of a qualification; schools, authorities, stakeholder bodies, laws, institutions, quality assurance, and qualifications frameworks. All countries have qualifications, so all have qualification systems. Qualification systems are the set of organisational arrangements in a country that work together to ensure that individuals have access to, and can choose and obtain qualifications that are fit for purpose, meet the needs of society, and offer opportunities for employment, recognition, career development, and lifelong learning.

While every country has a qualification system, an NQF is a specific instrument within a qualification system, and therefore not all countries have them.

All partner countries which are reforming their qualifications towards outcomes-based qualifications are using an NQF as the principal tool to achieve this change. But NQFs do not always succeed in linking different types of qualifications. Even with a framework that is conceptualised and agreed by stakeholders, the different sectors within a country’s education and training system may apply different principles for learning outcomes, quality assurance, and qualification standards. Such an NQF will be fragmented and not based on the common principles that should be an integral part of a common framework.

Partner countries’ qualifications and qualification systems are at different stages of development. We distinguis five stages of development, from the ad hoc stage where discussions about qualification reform is taking place but there are not yet plans for a policy or implementation programme, until the consolidated stage where curricula, assessment and learning adapt to new qualifications and individuals use new qualifications for career progression and mobility. (See the Annex on policy stage indicators).

In this chapter, we look at new and old ways of getting organised and how to make national qualification systems work. But first we need to get a common understanding of what we mean with ‘new’ qualifications.

2. A new understanding of qualifications

According to the European Qualifications Framework (EQF), a qualification is “the formal outcome of an assessment and validation process which is obtained when a competent body determines that an individual has achieved learning outcomes to given standards.” For many countries, this remains more conceptual than real. A new understanding of qualifications is spreading into policy documents and laws, but is not yet common among stakeholders, let alone the general public. The aim here is to be consistent in our understanding of the term ‘qualifications’, and to encourage partner countries to adopt internationally compatible definitions.

Other technical terms make the concept of qualification even more complex. For example, full vs part, higher vs vocational, or formal vs non-formal qualifications. Definitions of the terms ‘knowledge’, ‘skills’, and ‘competences’ can be equally confusing, particularly when addressing competences. Are competences only a matter of autonomy and responsibility, or much wider? Do they include attributes and attitudes? And do they cover an individual’s potential, or just their proven abilities?

There are important cultural differences affecting how far one can go with general and basic competences, or the extent to which qualifications can be composed of units. Some countries emphasise the importance of mastering a profession or trade, insisting that a qualification cannot be split into pieces. For them, the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Others are more pragmatic, putting the emphasis on the skills and competences that can be used for different career purposes. In many partner countries, as in some central European countries, there has been a strong tradition of professionalisation associated with qualifications. Recent transitions in partner countries have seen a process of de-professionalisation in which young people try to postpone specialisation, staying in education longer to keep their options open. Attainment levels have gone up and people are generally better educated, with improved generic skills, but this has not led to better qualifications. On the contrary, trust in existing qualifications has declined because of factors such as the proliferation of courses and qualifications, and the perceived gap between provision and labour market needs. At the same time, there has been a rediscovery of qualifications as a central policy issue, with a renewed emphasis on relevance, quality assurance, assessment, and recognition.

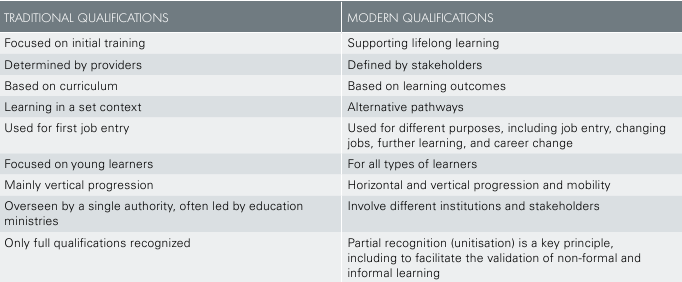

Many countries are moving towards integrated lifelong learning systems, and away from separate and often unconnected pillars for general education, VET, higher education, and adult learning. A national qualifications framework is a strategic instrument for facilitating lifelong learning, but even more fundamentally, the qualifications themselves can be the starting point for transforming learning processes, expressed in learning outcomes, as the products of education and training systems. The movement towards new qualifications as the core of integrated lifelong learning systems can be shown as a continuum, because rates of change vary from country to country. However, modern qualifications are significantly different from their traditional counterparts, as shown in Table 1.

Qualifications comprise learning outcomes defined in terms of knowledge, skills, and competences, for example, which provide measurable indicators against which an individual’s capabilities can be assessed. Work-related competences in occupational standards facilitate the definition of learning outcomes, and many partner countries have embraced occupational standards as a basis for developing relevant vocational qualifications. A learning outcomes approach can make the results comparable, and at the same time offer learners different pathways to achieve these results. But more attention must be paid to assessment and quality assurance in order to check that intended learning outcomes have been actually achieved.

Table 1. Modern and traditional qualifications

For providers, this means moving away from a traditional, norm-referenced approach where student performances are compared to each other, towards testing specific learning outcomes in national standards. While this reduces their ability to award qualifications at their discretion, learning outcomes allow providers more freedom in defining learning processes. Recognising that learning outcomes can be acquired through different pathways also enables the development of systems for the validation of non-formal and informal learning. Learning outcomes can facilitate the comparison of qualifications, if they are coherently expressed, particularly for those qualifications in affiliated areas that can be allocated to an identical level in a qualifications framework. This makes it possible in principle to compare qualifications that are developed and awarded by different institutions.

The view that qualifications do not matter, and that what is important is having the skills to succeed, is still heard. But this is a simplification that needs to be challenged. Skills are important, especially in continuing vocational training, but for someone to show that they possess a set of skills demands some form of portable currency, i.e. a qualification. Good qualifications capture what knowledge, skills, and competences people need in order to be equipped for the future labour market. Such qualifications are a necessity when people increasingly move between jobs and between national labour markets. A new understanding of qualifications should also cover part qualifications or units (where a unit is a specific set of learning outcomes) to facilitate validation of non-formal and informal learning. Qualifications establish the all-important link between education and work, creating a common language among providers, learners, and employers.

The NQF concept, promoted through the EQF, has turned existing concepts of qualifications in partner countries on their head. Qualifications have always been seen as the logical outcome of a curriculum, the end result of the learning process. But as our previous study demonstrated, better results start from learning outcomes, and curricula need to be developed from qualifications, not the other way round. Another change is that qualifications are being used as formal certificates, while people commonly still refer to someone’s qualifications as their competences. These are deeply-rooted differences in the perception of qualifications, and they are only gradually changing.

3. New versus old ways of getting organised

In many partner countries the whole set of necessary arrangements to qualify learners can perhaps best be characterised as being in flux. There is innovation taking place, and there are new laws, strategies, and regulations being adopted that embrace modern concepts of qualification. There are pilot projects and experiments in developing occupational standards, qualifications, and curricula. But most vocational qualifications are not yet based on learning outcomes and remain weak on assessment, and they have not been developed with systematic input from the world of work.

Where stakeholders from the world of work have started to engage, and are cooperating in developing standards and qualifications, capacities and resources are inevitably limited. Some countries get stuck at the legislative level. And countries cannot advance on the basis of voluntary cooperation between stakeholders alone; they need systemic approaches, in both the software (concepts) and hardware (operational arrangements) of qualification systems. They also need to review existing qualifications and develop hundreds of new ones. They need to establish repositories in the form of databases that are available to users, along with methodologies, guidelines, rules and regulations, procedures, resources, and institutions – and to build capacities in all of these components.

This does not imply that vocational qualification systems in the partner countries have been completely without links to the labour market. On the contrary, many countries, particularly in the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, have inherited systems of vocational qualifications that are intertwined with labour market regulations. For instance, the tariff-based qualification system of the former Soviet Union regulated all permitted occupations and job titles. The Classifier of Occupations was linked to handbooks of qualification characteristics that described the skill requirements for each occupation. These qualification characteristics were, in turn, the basis for developing vocational education standards and professionally-oriented higher education standards. National lists of educational programmes or specialisations determined which state education standards had to be developed. The state education standards contained the requirements for the provision, as well as for certification. Because they regulated the requirements for certification, they could be called the qualification standards. The qualifications that were obtained regulated access to occupations and jobs, and were part of the formal labour registration system. The diplomas that were issued after completion of the studies mentioned both the area specialisation and the ‘occupation’ (kvalifikaciya in Russian) that was obtained by the holder. People were subsequently registered by their qualification/ occupation in their workbook, the job registration booklet that every worker had, along with the related wage level, which would normally increase with their responsibilities after performance assessment. Qualification and wage level also determined working conditions and pension arrangements. Similar arrangements existed in the former Yugoslavia.

More than 25 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, much of this system survives in one form or another, particularly where there is still considerable wage employment. And even longer after widespread de-colonisation, elements of the former British and French education systems can still be traced in partner countries from the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean region.

4. Competing ministerial agendas

Qualifications are an important topic in both education and labour market policies. While education ministries have been focusing on curriculum reform, and in particular widening existing programmes, labour ministries have been trying to ensure that occupational descriptors reflect changing labour market needs. It is often the labour ministries that started to work with employers’ representatives or social partners on training programmes for job seekers and certificating adult learning. This must be seen against the background of growing unemployment and economic restructuring, requiring the development of better adult learning to support retraining and career change. These initial competency-based programmes and qualifications have also had some impact in curriculum reform in secondary vocational education, under the influence of donor projects. But although curricula have changed, qualifications have not always been affected. Qualifications are still defined by state educational standards, and remain the outcome of the same or similar development processes.

The new NQFs promote relevant, quality-assured, learning outcomes-based qualifications that can facilitate lifelong learning, career development, and labour mobility. But apart from regulated professions, qualifications are not generally seen as an instrument for labour market regulation. On the contrary, qualifications should be passports to a wide range of career, learning, and personal development opportunities. This is appropriate for people who are expected to change their job role more frequently, with traditional wage employment much less common.

The new NQFs promote relevant, quality-assured, learning outcomes-based qualifications that can facilitate lifelong learning, career development, and labour mobility. But apart from regulated professions, qualifications are not generally seen as an instrument for labour market regulation. On the contrary, qualifications should be passports to a wide range of career, learning, and personal development opportunities. This is appropriate for people who are expected to change their job role more frequently, with traditional wage employment much less common.

The NQF allows the attribution of levels to qualifications issued by different organisations. Based on their outcomes, qualifications can receive a level. The learning outcomes make it easier to compare different qualifications for the same occupational area or field of learning, issued by different institutions. Learning outcomes make it possible to compare the results of learning in different contexts. This challenges the monopoly of education ministries as providers and issuers of qualifications. Employers and labour ministries are particularly attracted to the idea of learning outcomes-based qualifications that are responsive to labour market needs. The debate is once more about qualifications and what you can do with them, rather than educational programmes.

In moving to a new concept of qualification systems, with NQFs at the core, many issues require clarification. For instance, if new qualification systems are developed to support lifelong learning, which qualifications should be part of these NQFs? How are qualifications managed and quality assured? How can different types of qualifications be linked? What should happen to existing or obsolete qualifications? Which parts of the old system can be continued, and which must change? Many of these questions can only be answered over time, when implementation is sufficiently advanced.

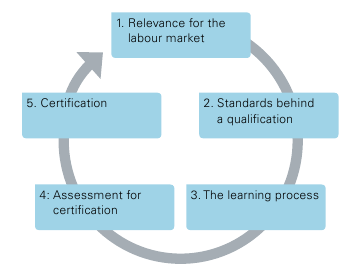

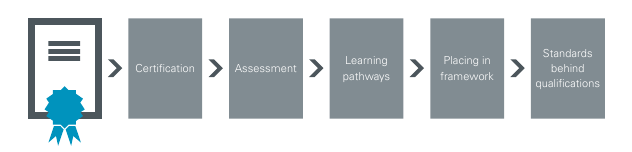

5. Making qualifications frameworks work

We see national qualifications frameworks as vital tools in the systemic reform of education and training systems in our partner countries. Moving from NQFs as a concept to functioning frameworks populated with qualifications is a first critical step. An NQF without qualifications in it will have no impact. But populating a NQF raises many issues such as: which qualifications are good enough to enter the NQF register, who can propose the qualifications for the register, who checks their quality and approves them and who manages the register? These are aspects of the wider qualification system, rather than the NQF itself. And these questions cannot be answered by one actor alone.

In the narrow sense, the NQF provides a skeleton of levels to which qualifications can be allocated. The NQF as a classification instrument is a tool for bringing order to the landscape of qualifications. This is an important function, and the NQF is becoming indispensable for modern qualification systems. It can facilitate the comparison of qualifications at national and even international level, and brings together everything in one organised structure. But to make qualification frameworks work we must address it as part of the wider qualification system, covering all the arrangements that affect how qualifications are designed and developed, how they are managed, and how they are used for learning, assessment, and recognition in the education system and the labour market.

The focus in this toolkit is more on the qualification systems, rather than on qualifications frameworks. Previous studies have not made that distinction very clear. The European Parliament and Council Recommendation which established the EQF makes the following distinction:

‘national qualifications system’ means all aspects of a Member State’s activity related to the recognition of learning and other mechanisms that link education and training to the labour market and civil society. This includes the development and implementation of institutional arrangements and processes relating to quality assurance, assessment and the award of qualifications. A national qualifications system may be composed of several subsystems and may include a national qualifications framework;

‘national qualifications framework’ means an instrument for the classification of qualifications according to a set of criteria for specified levels of learning achieved, which aims to integrate and coordinate national qualifications subsystems and improve the transparency, access, progression and quality of qualifications in relation to the labour market and civil society;

However, these definitions are problematic, as they try to be both comprehensive and brief. In the NQF definition, the classification function is clear, leading to an understanding of how it could be used to integrate and coordinate national subsystems. But this function is not fulfilled by the NQF alone. Instead, it requires the involvement of stakeholders and institutions. Can it really be claimed that NQFs improve “access, progression and quality of qualifications in relation to the labour market and civil society” if there is no involvement of actors in the system, or principles to guide the development and use of qualifications?

The first sentence of the qualification system definition, on the other hand, is so wide-ranging that it can include complete education systems. Meanwhile, the second sentence looks narrowly at the institutional arrangements and processes for quality assuring, assessing, and awarding qualifications. In the third sentence, subsystems might have been explained. Does this refer to qualification systems for general, vocational, higher education, and adult learning? Or is it sectoral or field specific subsystems, or systems falling under the responsibilities of different ministries and other entities?

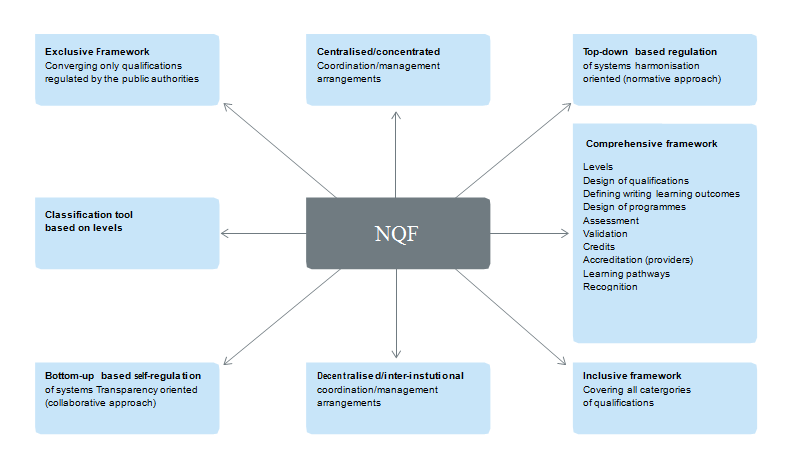

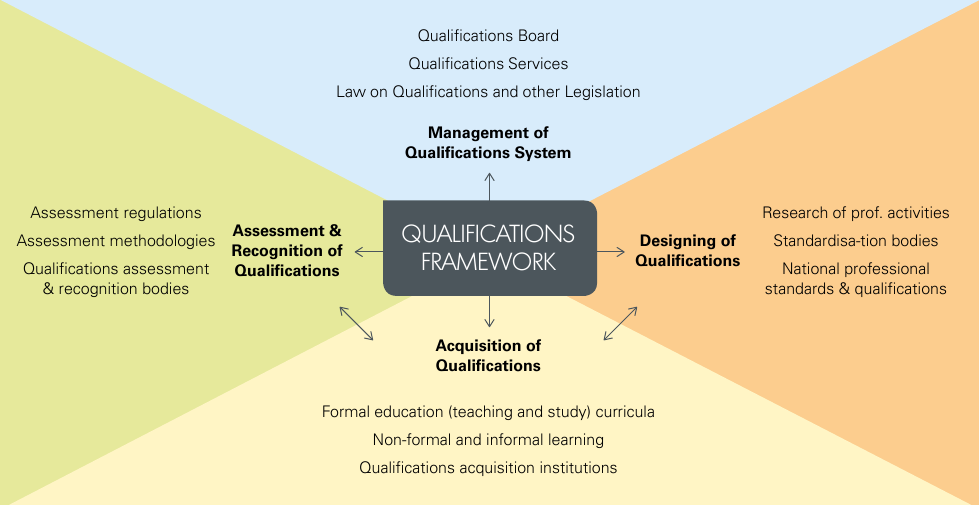

Figure 1. Different scope and characteristics of NQFs.

Figure 2. National qualification system of Lithuania.

The International Labour Organization explored these concepts further, asserting that the NQF as a driver of outcomes-based qualification systems could undermine the focus on strong education institutions. They highlight how NQFs in some English-speaking countries helped to create “distinctive features” that tend to separate the qualifications from the institutions which deliver them. They point out that “the nature and design of the NQF should be based on the goals that policy makers seek to achieve by introducing an NQF”.

Evidence from our partner countries shows that the development of outcomes-based systems is accompanied by efforts to improve provision, and that implementing new qualifications without improving curricula, provision, and teacher training is a dead-end that cannot produce more effective systems. Building on this evidence from partner countries, and beyond, affords the opportunity to look at how real, rather than ideal, qualification systems will be organised when countries move from traditional to outcomes-based models. In that sense, a better distinction between the framework and the system is vital, while avoiding comprehensive definitions that include overlapping aspects which are difficult to disentangle.

Figure 1 shows scope and characteristics of NQFs, which vary from a classification tool based on levels to a comprehensive framework. The latter includes the design of qualifications, principles of how learning outcomes should be described, programme design, assessment, validation, and quality assurance, along with levels. This identifies ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors (indicated by the arrows) in organising the qualification system, including the scope of the framework, coordination mechanisms, the degree of regulation, and the responsibilities of actors. As Figure 1 also suggests, the quality of qualifications is affected by how they are organised.

Figure 2 shows another schematic representation, depicting the NQF playing a key role at the heart of the Lithuanian qualification system. The NQF brings order to the design and acquisition of qualifications, and to assessment and recognition, thereby supporting management of the system as a whole. This model is organised around processes that are not system-specific, as it describes functions rather than mechanisms and actors.

6. Towards sustainable qualification systems that can produce better qualifications

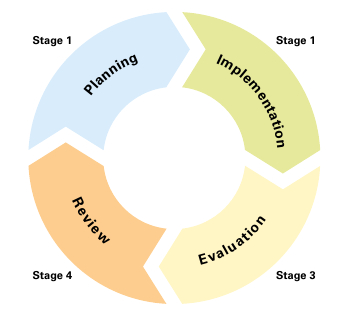

Qualification systems are effective if the organisational arrangements work properly together to achieve the outcomes described above. This means creating systems of interdependencies that can generate high-value qualifications, the effects of which can only be measured when individuals have actually been certificated. However, improvements to the way systems are organised and structured can be made now. We have identified four foundation components in the organisation of a qualification system, which are common to all systems and are independent of local or other specific environmental factors.

These are:

1. The legal and regulatory context

2. Effective stakeholder dialogue

3. Institutional arrangements, and

4. Quality assurance arrangements.

Rather than looking at national differences we wish to identify the commonalities for successful systems. Within these four fundamental building blocks, then, we are looking for the most effective formula or set of arrangements.

Laws or regulations stipulate functions of the NQF and criteria for qualifications, and allocate tasks and responsibilities to associated institutions. They also regulate the rules of the game so that each party can play their role fully within the system. Laws or regulations often specify the practical purpose of the NQF, articulating the basic requirements for qualifications that are part of the framework, their relationships, and how they are used. Legislation is needed to enable reform and confirm changes in policies, and to regulate the qualification system. This helps to facilitate the quality and comparability of individual qualifications, and ensures the necessary resources and capacities are set aside to move from pilots to system-wide implementation. Laws can be enablers, but can also create rigidities that only inhibit reform. Legislation is a process, and laws are likely to be amended during the early years of implementation. A single act, legislating the NQF, the qualifications agency, or standards and vocational qualifications, often proves a blunt instrument. Education or labour laws need to be adapted as well, to integrate the principles of the qualification system reforms.

Effective stakeholder dialogue is about making sure that all are committed to making better qualifications, and are engaged in the necessary processes. This doesn’t mean getting as many organisations as possible involved, but making sure that all those who need to be involved can participate, understand what is expected from them, and know how to contribute. Stakeholder involvement can strengthen ownership and relevance of qualifications and their acceptance in both the labour market and the education system. Stakeholders can be involved at different levels, in setting policies or in implementation. It is important to note that the private sector is the main motor for employment growth in partner countries, even if the public sector remains an important part of national economies. Generally, the participation of the private sector in qualification systems is weak. The problem is often recognised by public actors, who show readiness to legislate, organise, and even subsidise private sector involvement. The main challenge is to engage representatives from the private sector effectively in a structural capacity to work on improving qualifications. Another essential group of stakeholders is education and training providers. They can become the main obstacle to system-deep reforms if they have not been engaged in the process.

The responsibilities and possible institutional arrangements that can support effective implementation need to be clarified, reviewing both existing institutional capacities and the need for additional capacities. In some cases, this will include creating new, specialised institutions for coordination and quality assurance, or for developing, assessing, or awarding qualifications. Institutions are needed to ensure a professional process for the development and use of qualifications; to organise the involvement of stakeholders; and to coordinate between different actors at different levels. In so doing they can empower the developers and users of qualifications to fulfil their functions effectively, and to externally quality assure the work performed by different actors so that qualifications are trusted.

The main function of quality assurance is to provide more confidence in qualifications and the competences of people who hold qualifications. Quality assurance focuses in particular on two aspects; ensuring that all qualifications that are part of the NQF register are relevant and have value, and that all the people who are certificated meet the conditions of the qualification. Quality assurance of the qualification system in its totality also plays an important role in regularly reviewing the functionality of the arrangements, as priorities for implementing the NQF are frequently changing. The issue of quality is an integrated part of the system of governance, rather than a separate issue.

This is by no means a new insight, as the ‘regulatory’ approach always had within it the issue of regulating the qualifications and the actors involved in qualifications frameworks. Moreover, since the lack of trust in existing qualifications and arrangements is one of the main drivers for greater transparency, a stronger focus on learning outcomes, and the comparability of qualifications, quality has never been de-coupled from legal and institutional arrangements.

7. Conclusions and recommendations

At the heart of our overall rationale for getting organised is the belief that comprehensive, coherent systems produce better qualifications. This coherence can be achieved through the development of the four foundation components identified above, starting with legislation.

Recommendations

- Promote a common understanding of qualifications.

- Don’t stop at developing an NQF – they are a necessary but not sufficient condition for systemic reform.

- Different systems need to be fit for purpose, that’s why they are different. To learn from others, look at the commonalities rather than the differences.

- Review existing qualifications before you develop new ones.

- Consider whether all qualifications are fit for lifelong learning.

- Make all qualifications available publically through an online database.

- Stakeholders from the world of work must have a role, as a prerequisite for systemic change.

- Recognise the inter-dependencies between actors in the system. No single actor can achieve change alone.

- Identify appropriate progress indicators and monitor them.

Access the self assessment tool for chapter 1

LaunchChapter 2. Legislation for better qualifications: support or obstacle?

Summary

- Key parts of legislation for better qualifications

- The legislative process

- Striking a balance between tight and loose legislation

- Stakeholder involvement in the development of legislation

- Ensuring that laws are implemented

- Conclusions and recommendations

1. Key parts of legislation for better qualifications

To put it simply, countries use legislation to regulate things they want to change. The primary aim of legislation is then to specify what is going to be changed, who is in charge, what resources are available, and how responsible bodies are held accountable for what they are doing through monitoring and reporting.

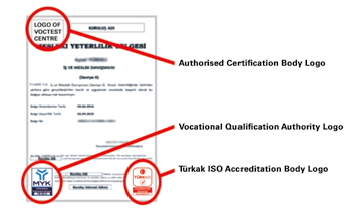

We researched legislation in eleven countries, and found a wide range of qualification-related laws and by-laws. Our scrutiny of these countries’ legislation shows that many start with developing and regulating a national qualifications framework; others start with establishing a qualifications institute; and then there are countries that create a new qualification system outside the education system. For example, Turkey and Estonia created new qualification systems based on occupational standards. For Turkey, the legal lever for this reform was the law on the Vocational Qualifications Authority; while for Estonia, it was the Occupational Qualifications Act.

We also looked at the direct impact of the legislation, and asked some basic questions: Has the law been implemented? Has it achieved its purpose? Has there been a knock-on effect on other laws? And, for laws already in place for a couple of years, has the law improved the quality of qualifications and changed the lives of individuals? If the law has not been implemented, why? What is affecting or blocking its implementation?

In very general terms we can conclude that laws addressing institutions and new types of qualifications have more direct impact than a law on the NQF. But our main lesson learned is that reform processes aimed at better qualifications require eight key parts of legislation that cannot be isolated from each other. Key parts 1 to 3 regulate the foundations, while key parts 4 to 8 regulate different aspects of qualifications.

Key part 1: Regulating purposes and principles

The purpose of a law answers the question, what do we want to achieve with this law? The principles describe the contextual base of a law and answer the question, why do we need this law? Purpose and principles can be limited to the direct topic of the law.

For instance, the purpose of a law on a national qualifications framework will be to regulate the structure (the levels and descriptors, and types of qualifications included); institutional arrangements; and quality assurance. The principles of such a law might be to promote lifelong learning and to match qualifications with labour market and societal needs.

A law can cover a wider range of purposes and principles, positioning a qualifications framework or qualifications authority within a reform agenda. Ideally, the purposes and principles of a new law are based on a national strategy that has been defined and agreed in dialogue with a wide group of stakeholders.

Key part 2: Regulating institutional arrangements

To be implementable, each law should have a section on institutional arrangements that regulates the roles and responsibilities of the competent bodies, and identifies the resources to execute the provisions in the law. For example, the Kosovo Law on National Qualifications (2008) regulates the status of the National Qualifications Authority (NQA) as an independent public entity, the membership of its Governing Board, the main procedures of its meetings and decision-making, and its management and reporting provisions.

The law defines that the NQA is responsible for the development of policies and strategies for the establishment and implementation of the national qualification system. The law also defines a range of functions of the NQA in regulating the NQF (including design and approval), and in regulating the awarding of qualifications. The law stipulates the responsibilities of the NQA as follows:

- Establishment and maintenance of a comprehensive qualifications framework

- Regulation of the awarding of qualifications in the framework, with the exception of qualifications which are regulated under the provisions of the Law on Higher Education and qualifications explicitly regulated under the provisions of other legislation.

Key part 3: Regulating stakeholder involvement

Laws can regulate the roles and tasks of stakeholders in implementing aspects of a qualification system, as part of its institutional arrangements, as the following examples demonstrate.

The Occupational Qualifications Act of Estonia (2008) delegates many decision-making rights and responsibilities in the occupational qualification system to professional and sectoral bodies. The Vocational Education and Training Act of Lithuania (first issued in 1997) stipulates the establishment of sectoral professional committees as tripartite bodies responsible for the approval of sectoral occupational standards. The Implementing Regulation on the Establishment, Duty, and Working Principles of Sector Committees of Turkey defines the procedures for the establishment of sector committees, their governance and work procedures, and their functions. It foresees sector committees as collegial multipartite entities providing counselling, and executing review and quality assessment of occupational standards. Sector committees will provide the expertise and feedback of sectoral stakeholders in a more centrally governed national system of qualifications.

But legislation can also be an obstacle to stakeholder involvement. Trade union representatives in Tunisia have indicated that a crucial reason for slow progress in their country’s national qualification system reform is that it is still based on legislation from the pre-revolutionary period. For example, according to the current legislation, continuing vocational training (CVT) is an object of government regulation, while employers and trade unions have no rights to define the contents and organisation of provision of CVT. This issue is widely discussed amongst policymakers and social partners, and different solutions are proposed, such as the introduction of an individual right to CVT and the recognition of informal and non-formal learning. These ideas cannot be implemented until the current legal basis is changed.

Key part 4: Regulating development of qualifications

Regulating the development of qualifications is aimed at improving their quality, making qualifications comparable, and introducing national standards and learning outcomes to ensure relevance for the labour market and society.

Regulations concerning the development of qualifications are generally part of laws with a broader scope; for instance, laws that regulate a qualifications authority and an NQF, or a wider VET law. These laws regulate the principles of the design and development of qualifications, introducing national occupational standards. Examples include the respective laws of Kosovo,Turkey, and Lithuania.

More detailed provisions regarding methodologies and requirements for the approval and updating of occupational standards are regulated in by-laws (secondary legislation).

Legislation about the development of qualifications normally refers to vocational qualifications. Higher education institutions are autonomous and develop their own programmes, which are subject to quality assurance via HE accreditation processes.

Key part 5: Regulating the national qualifications framework

A national qualifications framework brings order to the landscape of qualifications, cutting across the entire education and training system. Therefore, one overarching NQF law should regulate the main features of the NQF. Many countries have a separate NQF law or decree, while in some the NQF is part of a broader law that also regulates other parts of the qualification system (as in Kosovo, France, Hong Kong, and Estonia). Increasingly, NQFs are integrated into legislation of educational sub-systems, such as in Albania’s new laws on HE and VET (draft), which both refer to the Albanian Qualifications Framework.

The features of a national qualifications framework that should be regulated include:

Scope. Which education sub-sectors and types of qualifications are included in the NQF? Are qualifications that are not the outcomes of formal education included?

Structure. That is, the levels and level descriptors in the NQF.

Management both of the NQF itself and the implementing institutions.

Database. A register or database of qualifications, and its link with the NQF. Does the register/database only contain qualifications that are included in the NQF or other qualifications – for example, legacy qualifications, that are not any longer awarded, but held by many people in the labour market?

Relationship with other instruments. Is the NQF the national instrument for structuring and classifying qualifications in a country, or are there others? How are different classification systems aligned? For example, former Soviet countries like Belarus and Kazakhstan are developing new NQFs while they have an existing qualification system (the former Soviet tariff-based qualification system; see Chapter 1) which guarantees access to further learning, to jobs, and to career development, salaries, and pensions.

Access. To qualifications, and to the horizontal or vertical progress between qualifications and qualification levels, and to the transfer of credits.

Learning outcomes. The basis for qualifications.

Quality assurance. Both of the qualifications in the NQF and the framework itself. What are the procedures for inclusion of qualifications (see Chapter 4)?

VNFIL. Validation of non-formal and informal learning (see key part 7, below).

EQF. In other words, linking to the wider European dimension allowing transparency, mobility and comparability.

Key part 6: Regulating quality assurance of qualifications

This means regulating the processes to maintain the quality of qualification standards, assessment, and certification. It also includes regulating the bodies that are responsible for quality assurance of qualifications, and the coordination between these bodies. But quality assurance of qualifications also refers to procedures and criteria for the inclusion of qualifications in an NQF and database or register. All laws that regulate parts of qualification reform should have a section on quality assurance, as illustrated by the following examples.

Law on the Albanian Qualifications Framework, Albania: “A qualification is awarded when a competent body decides, by means of a quality assurance assessment process, that the individual has reached the specified standards.”

National Qualifications Law, Kosovo: “Carry out external quality assurance of assessments leading to the award of qualifications in the NQF; implement internal quality assurance of assessments leading to approved qualifications, to ensure consistency in the application of standards.”

NQF Law, former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia: “Quality Assurance in the application of the Macedonian Qualifications Framework applies to the quality of qualifications in the Framework, the procedures that lead to acquiring qualifications, and the degrees, diplomas, credentials, and certificates that are awarded to the participants who have acquired the qualification.”

The decree enacting the Turkish qualifications framework (TQF) has an extensive section on quality assurance. One of the fundamentals of the TQF is to ensure effective cooperation among the bodies that are responsible for the quality assurance of qualifications. The article on quality assurance of qualifications states: “All quality assured qualifications that have been acquired through education and training programmes as well as other ways of learning shall be included in the Turkish Qualifications Framework. Criteria for ensuring the quality assurance of the qualifications shall be determined by the Authority.”

This is followed by articles about responsibilities for quality assurance for different types of qualifications: those under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education; in higher education; under the responsibility of the Vocational Qualifications Authority, in VET; and other qualifications. The section on quality assurance ends with an article about the qualifications database: “With the qualifications being included in the framework, a Qualifications Database where all the qualifications agreed to be included in the framework are officially recorded and information regarding the qualifications is stored shall be created, and it shall be regularly updated by the Secretariat.”

Key part 7: Regulating validation of non-formal and informal learning (VNFIL)

Validation of non-formal and informal learning allows individuals to demonstrate what they have learned outside formal education and training, so that they can use it in their careers and for further learning.

The EQF recommendation of 2008 speaks about validation of non-formal and informal learning in general terms, and recommends that member states promote non-formal and informal learning. The EU recommendation on VNFIL of 20126, however, sets specific goals for EU members, stating that:

“[T]hey have in place, no later than 2018… arrangements for the validation of non-formal and informal learning which enable individuals to:

(a) have knowledge, skills and competences which have been acquired through non-formal and informal learning validated(…);

(b) obtain a full qualification, or, where applicable, part qualification, on the basis of validated non-formal and informal learning experiences(…)”

This requires a link between the VNFIL arrangements and the qualifications in a country’s NQF. In 2014 Cedefop explored this link in its European inventory of VNFIL, which includes 36 reports from 33 countries, including non-EU countries Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, and Turkey. Separate reports cover the French-speaking and Dutch-speaking communities in Belgium, and the UK nations of England, Scotland, and Wales. Cedefop divides countries into three levels:

High: Learning acquired through non-formal and informal means can be used to acquire a qualification in the NQF and/or can be used to access formal education covered in the NQF (19 countries in 2014).

Medium: A link between non-formal and informal learning and the NQF is under discussion (17 countries in 2014).

Low: There are no discussions on the establishment of this link (0 countries in 2014).

In France, validation is completely integrated in the NQF; a qualification can only be registered in the national qualifications framework (repertoire national des certifications professionnelles) – which is the basis of the NQF – if it is open to validation. In all four nations of the UK, the link is also tight. In many countries the link is under discussion. Some of these countries do not yet have an operational NQF in place, nor arrangements for VNFIL. If they wish to follow the EU Recommendation on VNFIL, ETF partner countries8 should include provisions about VNFIL in their NQF legislation and include provisions about the NQF in their separate VNFIL legislation.

Key part 8: Regulating recognition of qualifications

The terms ‘validation’ and ‘recognition’ are often used interchangeably, yet they have different meanings. Validation refers to the process of confirmation of an individual’s knowledge, skills, and competences; recognition refers to the external recognition of that qualification – in other words, the piece of paper issued to that individual. Two types of recognition are relevant for qualification system legislation.

1. Recognition of foreign qualifications for regulated professions. Based on the EU Directive 2005/36/EC on the recognition of professional qualifications for regulated professions, EU member states need legislation to ensure smooth and unequivocal recognition of foreign qualifications in regulated professions. The scope of such laws is limited. It stipulates the norms and procedures for recognition of professional qualifications acquired in foreign countries.

2. Recognition of higher education qualifications (for non-regulated professions), under the Lisbon recognition convention. The Lisbon convention of 1997, developed by the Council of Europe and UNESCO, has been ratified by most European countries. The convention requires that holders of qualifications issued in one country shall have adequate access to an assessment of these qualifications in another country. The convention defines detailed procedures and arrangements for the assessment and recognition of qualifications. No such convention yet exists for VET qualifications.

2. The legislative process

Now that we have seen which key parts require legislation in a systemic reform process towards better qualifications, let’s look at the legislative process, which is framed by a series of core questions: Where to start? How to align old and new legislation? How to link framework laws to more specific laws? And how to ensure coherence between qualification systems, education and training systems, and the labour market?

Reforming qualifications involves many issues: developing qualifications based on occupational standards; involving the world of work in qualifications development; introducing quality assurance of qualifications alongside quality assurance of providers and programmes; establishing a national qualifications framework to create order and transparency in types and levels of qualifications; and creating a database to make information about qualifications accessible to the public.

Such reform processes can take up to ten years and are difficult to plan in a linear fashion. Does it matter where you start the reform process and when you start with legislation? You have to start somewhere! As a basic rule, you can legislate when key stakeholders have a common agreement on the direction of the needed changes. Therefore, the best advice we can give is to start with a strategy for qualifications reform. This strategy should analyse the main problems you want to solve and what is required to solve them. Is there a lack of trust in qualifications by end users? Or a mismatch between the supply of qualifications and demand from the labour market? Or are lifelong learning opportunities blocked by a lack of access and permeability of the learning opportunities that lead to qualifications? If there is consensus about the main problems and solutions, you can prioritise and plan actions in different stages. Legislation can be built from there; the first legislation could focus on something that has an immediate impact. Legislation is often a prerequisite for making things happen, so don’t delay any necessary legislative process.

Laws are not forever

Laws are made for the future, but are not forever. Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine are now reviewing and completing NQF laws that were developed to start qualifications reform a couple of years ago. While these NQF laws played an important role at the beginning of the reform of individual qualifications, they have not contributed to clarifying the relationships between different qualifications and bringing order into the framework. These countries are now reformulating their NQFs to make them more functional, and to clarify relationships between qualifications at different levels.

The overall approach that is taken and the chosen starting point are not the decisive elements in implementing qualifications reform. Instead, the decisive elements are, first, that there is an identified need for qualifications reform; second, that different pieces of legislation are consistent with each other; third, that what is to be regulated is realistic; and – perhaps most critically – that all of this can truly be implemented.

Aligning old and new legislation

Every country has an existing legal framework, so it is not possible to start from a blank slate when legislating qualifications reform. A major challenge is ensuring that old and new pieces of legislation are aligned. Old and new laws often co-exist for a period of time, regulating different components that function in parallel with each other. This becomes problematic when laws are contradictory, creating overlapping competences in some aspects and ‘empty spaces’ in others. Consistency of legislation is especially important for implementation. Fragmented legislation makes arrangements unclear for local actors who have to implement them.

There are two main options when aligning old and new legislation; a country can either adapt existing laws by making amendments and constructing new by-laws, or it can develop a completely new legislative framework. To decide whether to adapt existing legislation or draft new legislation, you should have a good overview of the existing legislation. This requires a mapping exercise of all relevant laws and by-laws. The mapping should include an analysis of which pieces of legislation support the reform and which are contradictory. A decision can be made about restructuring the legislation, based on this analysis.

In 2015 Albania started drafting a new VET base law, after mapping the existing VET legislation. The new VET Law, after adoption in 2016, will replace the old law which dates from 2002. This old law has been amended several times, but still has many restrictions. Too many by-laws accumulated over the years have resulted in fragmentation. Due to the many amendments and new regulations, it is almost impossible to keep an oversight. Different laws regulate VET and have created overlapping competences or contradictions in some aspects, and gaps in others. Despite the multitude of regulations, many things remain unclear for the7 local actors who have to work with and implement them.

The new VET Law will support current reforms in the VET system and will be aligned with the Law on the Albanian Qualifications Framework (AQF) that has recently been revised too. A package of secondary legislation for implementation will be added to both the new VET Law and the revised AQF Law. The new legislation is part of the action plan of the National Employment and Skills Strategy 2014-2020. (See also how stakeholders were involved in development of the new VET law in Albania, in section 4 of this chapter).

In Georgia, implementation of the NQF and related reform led to revision and redrafting of the existing laws. According to the representative of the Department of VET at the Ministry of Education and Science, one of the core motives of the recent changes of legislation is to address a misfit of legal acts with national strategies. For example, the existing Law on VET does not fit with the national strategy for development of VET in 2012-2020, which foresees implementation of open, inclusive, modern, and development-oriented vocational education.

Therefore, the Ministry decided to draft a new Law on Vocational Education and Training. This law is targeted at solving one of the major problems and shortages of the VET system, namely the absence of permeability between initial VET and higher education pathways. This makes VET a dead-end from a lifelong learning and careers perspective, because VET students cannot acquire secondary education and access higher education after graduation. Another important planned change is the integration of the current, rather separate, sub-frameworks of the NQF into one comprehensive qualifications framework. This responsibility is delegated to the National Centre of Education Quality Enhancement. Social partners are also actively involved in this process. (See also how stakeholders were involved in development of the new VET law in Georgia, in section 4 of this chapter).

Primary and secondary legislation

Legal arrangements differ from country to country, but usually start from the constitution that sets out the powers and functions of the parliament or assembly, the government, ministers, and so on. The constitution is the principal source of law. Constitutions will generally define the division between legislative and executive (and judicial) powers, distributing authorities among several branches. Legislative power is the authority to make laws. The legislative branch of government in parliamentary systems is the parliament or assembly. Laws that are adopted by parliament or assembly are primary laws, setting out general principles.

Executive power is the authority to enforce laws and to ensure they are carried out as intended. The executive branch of government includes the head of state (president) and/or the head of government (prime minister) and ministers. Most countries have primary laws on VET and higher education, adopted by parliament and signed by the president. Then the president, or the council of ministers, or the minister of education (or equivalent) will make detailed provisions through secondary legislation. This can be in the form of decrees, orders, by-laws, or regulations, with the exact title depending on the legal system of the country.

Summarised: Primary legislation sets out general principles and is adopted by parliament or assembly. Secondary legislation defines detailed provisions based on the general principle, and is the authority of the executive branch of government (head of state and ministers). For example: Turkey’s Primary Law on Vocational Qualifications Authority (2006, amended in 2011). Implementing regulations on the development of occupational standards and the establishment of sector councils, the amended law of 2011 set out the principles of the Turkish Qualification Framework (primary law). The TQF regulation with detailed provisions was adopted in 2015 (secondary legislation).

Kosovo’s Law on National Qualifications (2008). This law has a broad scope, covering the establishment of a national qualification system based on a national qualifications framework regulated by a national qualifications authority. The law is supplemented with a range of administrative instructions (secondary legislation) for detailed provisions. NQFs are mostly legislated by resolutions or decrees, but smaller countries like Albania and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia have adopted NQFs through primary laws. The amount of detail found in primary laws varies widely from country to country, as we shall see.

3. Striking a balance between tight and loose legislation

Striking a balance between tight and loose legislation is not easy. There are examples of very tight or rigid legislation, and examples of loose or even no legislation. Most legal systems are mixed systems, with some elements of both tight and loose arrangements. Which way the scales tip depends largely upon the balance of powers and the division of responsibilities between stakeholders in a country, and on its cultural heritage.

Typical examples of loose legislation are found in the English-speaking world, where governments have been less inclined to legislate (prescribe) what qualifications should look like. Initiatives to develop qualifications come from private actors based on the principle that ‘everything is allowed unless it is forbidden’. The market regulates the number and quality of qualifications. High value qualifications are the result of actors in the market acting in freedom and looking for the optimal way of defining qualifications. Qualifications compete with each other, and consumers will choose those that offer the best value for money.

Not surprisingly, the construct of qualifications frameworks originated in Anglo-Saxon countries to regulate this free market of qualifications. The UK introduced qualifications frameworks to help employers compare the many hundreds of qualifications available. Currently the UK has five qualifications frameworks that together accommodate the majority of qualifications in use in the various education, training, and lifelong learning sectors.

A typical example of loose legislation is the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF), which uses common principles set out in a handbook. Although its constituent parts include regulatory frameworks, the SCQF is a voluntary framework. It uses two measures, SCQF Level and Credit Points, to help with understanding and comparing qualifications and learning programmes. Another example of loose legislation is the Framework for Higher Education Qualifications (FHEQ) in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, with the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) as the external quality assurance body. In the FHEQ, universities are responsible for developing their own qualifications and may use their own approaches as long as they can justify them. Loose legislation fits in the Anglo-Saxon Common Law tradition. Legislation is built incrementally around individual cases that are generalized to a larger area, creating precedence.